Making an Early Bow

Elizabeth Le Guin interviews Ralph Ashmead, specialist in early music archeterie.

Copy of anonymous violin bow, mid-18th century. Ironwood and scrimshaw mammoth ivory.

In the last ten years, the San Francisco Bay Area has flourished as an important centre for Early Music. The Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, headquartered in San Francisco and directed by Nicholas McGegan, enjoys a solid success with critics and public. No Philharmonia rehearsal-set would be quite complete without an appearance from bow maker Ralph Ashmead. Entering the rehearsal hall unobtrusively with two slender briefcase-sized boxes, he sits and listens attentively until the break, when the string section of the orchestra descends upon him with a kind of fierce enthusiasm, to see ‘what Ralph’s got this time’.

The boxes contain a stunning selection of violin, viola, and cello bows, in a variety of shapes, sizes and colours that nearly defies description: from tiny, short ‘stiletto’ bows, used to play the music of Monteverdi and his contemporaries, to fantastical Baroque bows with fluted sticks in brilliantly figured snakewood and sculpted frogs in fossil bone, to late 18th century, ‘transitional’ bows in a seemingly endless array of designs, weights and balances. The rehearsal period becomes a forum for the testing and discussion of bows, sometimes lasting several days; and while it’s not usual for Ralph to make a sale or two during his visits, he’s there for a more important reason – gathering and sharing information with his customers, listening to his bows being used in a working situation, and getting and giving feedback.

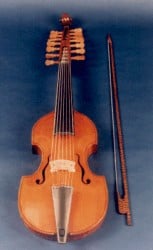

Viola d’Amore, 1985

7 +7 sympathetic strings

Curly koa & ebony

Baroque violin bow

The first instruments I made were lutes and guitars; than I branched out into making viola da gambas and violins. In 1983 I returned to the Bay Area and discovered I couldn’t find bows for my instruments! A local string teacher encouraged me to make some early bows. I realized that bow making really fits my personality and my skills: I enjoyed the intricate parts. There are only a few ornaments on the bows and they have to be perfect. Something in me just clicked with that.

1983 was a good year to come to the Bay Area; the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra was just starting up and people were needing bows. Also, the San Francisco Early Music Society concert series was bringing in Early Music specialists from all over the world. I was able to interact and do business with groups like the English Concert, Academy of ancient Music, Orchestra of the 18th Century, Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra and soloists like Jaap Schroeder and Stanley Richie.

When I come and watch a group play, I see that this bow’s working for that person, but not for that one. Maybe one person’s tightening it up more or less, maybe they’re choking up on it differently, or maybe it’s being used on a bigger instrument, or with a smaller person. There are all these little variables. Not every bow is right for every player. I’ve found over the years that I can get incredibly different reactions from musicians trying or using a given bow! Sometimes I’ll get a postcard from somebody saying, ‘Hey this bow’s really teaching me a lot!’ Maybe they bought something they weren’t totally sure what to do with in the beginning, they had to grow into it.

Now I’m in a nice comfort zone – not that I don’t make mistakes still! – where I don’t feel afraid to have 20 people try a bow and not like it. There might well be a 21st person who just knows how to handle that particular stick.

I like to think I’m not much different from bow makers back in the 17th and 18th centuries. They were constantly experimenting. Of course, I have a duty to maintain historical accuracy in copying old bows; but I also want to accommodate the needs of living players. So I do experiment. I make subtle changes, just as they might have done.

One of the joys of making early bows is the variety. For instance, 1750-1800 was an incredibly rich and varied time in the history of bow design. You can tell that makers were working feverishly to keep up with the demands of the new playing styles. And as with any experimentation, there are failures, but considering the huge range of woods, head-styles and cambers they were using, they created some beautiful successes.

Baroque bows

Snakewood & rosewood

In the early Baroque period, it’s a bit limiting just to go by the few existing bows in museums. I’ve had to come up with some designs based entirely on old paintings in order to ‘fill in’ certain time periods. It’s natural for people to want to alter things to the way they feel. In fact it’s more or less inevitable – no matter how much you may want to copy something, it’s going to come out like you.

I think this freedom is what drew me to early instruments and bow-making. There’s the inevitable vagueness of when, how, why and who made a particular old bow. The early Baroque ones were rarely, if ever, stamped with a maker’s name, and even with later bows we’re left with a lot of educated guesswork as to when and where a given bow originated. And then there’s the interesting issue of what players might have been using at a given time. There’s that famous lithograph of Paganini from around 1850 , using a straight, early-transitional bow, a design that was supposedly out of date by then. All these unknowns and variables leave me a window of opportunity in which to play around within the historical framework and come up with interesting variations on themes. [Another factor is the] kind of music the bow’s going to be used for. The periods I take my bow designs from had music that ranged from folk fiddling to heavily ornamented, refined court music. One really interesting development has been that a lot of fine contemporary Irish and Scottish folk-fiddlers are starting to realize that early bows are perfect for their dance music. They don’t really need the power and length of a full-sized bow, and these are lighter and easier to handle. A few really great players, Alasdair Fraser being one, have started pushing for this. After all, a lot of the best old Scottish and Irish fiddle tunes do come from the 17th and 18th centuries…

One slight difference with regard to olden times is that I use only fossil mammoth or walrus ivory, or fossil bone, instead of elephant ivory. And the simpler models just have wooden frogs and buttons.

I do enjoy making modern perambucco bows, and I feel there’s room for some of the early bow-making techniques there. For instance fluting, which was commonly used in Baroque bows – grooves were gouged out of the facets on the stick. It’s a great option between round or octagonal sticks, because it allows the use of heavier woods like snakewood or ironwood – which make beautiful bows – it reduces the weight of the stick but retains most of the stiffness. I think it’s unfortunate that fluting died out.

Also, I hope to start incorporating some of the beautiful early designs of fogs and buttons in my modern bows. Stay tuned!

Elizabeth Le Guin is a Baroque cellist, founding member of the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and musicologist, living in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Copyright © 1993 The Strad Magazine